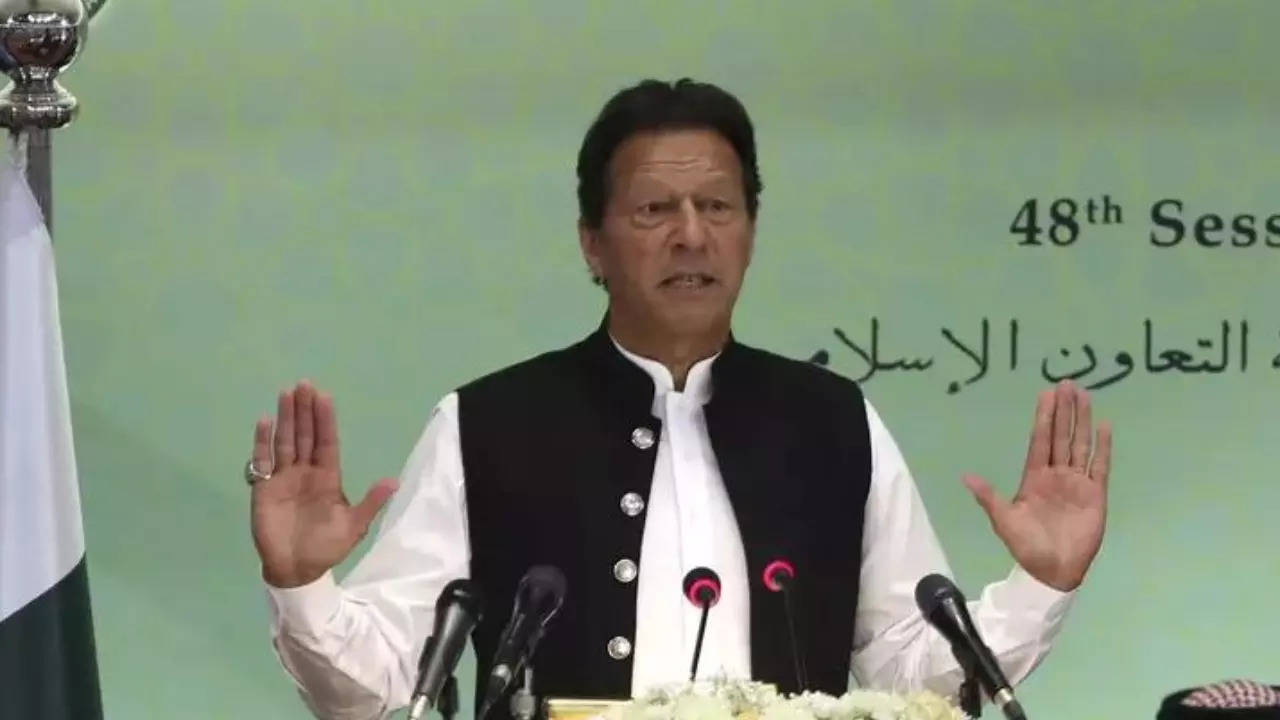

East Pakistan Prime Minister Imran KhanThe cricketing hero-turned-politician, who was arrested on Tuesday, hit a decade-high of popular support amid inflation and a cripple financial crisis before his eviction last year.

Even after being injured in an attack on his convoy in November, the 70-year-old has shown no sign of slowing down as he led a protest march in Islamabad demanding general elections.

Khan had postponed for months to arrest He has several cases registered against him including charges of inciting mobs to violence. There were massive protests against previous attempts to arrest him.

Khan was ousted as prime minister in April last year amid public frustration over high inflation, a mounting deficit and endemic corruption, which he had promised to root out.

The Supreme Court overturned his decision to dissolve parliament, and his defection from the ruling coalition meant he lost the vote of no confidence that followed.

This put him on a long list of elected Pakistani prime ministers who have failed to see out their full terms – none since independence in 1947.

In 2018, the cricket legend, who led Pakistan to its only World Cup win in 1992, rallied the country overseas behind his vision of a corruption-free, prosperous nation. But the firebrand nationalist’s fame and charisma were not enough.

Criticized for being under the thumb of the once-powerful military establishment, Khan’s ouster came after deteriorating relations between him and the then army chief General Qamar Javed Bajwa.

The army, which has had a major role in ruling Pakistan for nearly half its history and gaining control of some of its biggest economic institutions, has said it is neutral towards politics.

sudden rise

But according to local polls, Khan is again among the most popular politicians in the country.

His rise to power in 2018 comes two decades after he first launched his political party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), or Pakistan Movement for Justice Party, in 1996.

Despite his fame and status as a hero in cricket-mad Pakistan, the PTI languished in Pakistan’s political jungle, winning no seats other than Khan’s for 17 years.

In 2011, Khan began attracting huge crowds of young Pakistanis disillusioned by local corruption, chronic power outages, and crises in education and unemployment.

He gained even more support in the following years, with educated Pakistani immigrants quitting their jobs to work for his party, and pop musicians and actors joining his campaign.

His goal, Khan told supporters in 2018, was to transform Pakistan from a country with “a small group of rich and a sea of poor” to “an example for a humanitarian system, a just system for the world, what is Islamic”. . welfare state”.

He was victorious that year, marking a rare ascent to the pinnacle of politics by a sporting hero. However, observers cautioned that his worst enemy was his own rhetoric, which sent supporters’ hopes sky high.

playboy to reformer

Born in 1952, the son of a civil engineer, Khan grew up with four sisters in an affluent urban Pashtun family in Lahore, Pakistan’s second largest city.

After a privileged education, he went to the University of Oxford where he graduated with a degree in Philosophy, Politics and Economics.

As his cricket career flourished, he developed a playboy reputation in late 1970s London.

In 1995, he married Jemima Goldsmith, daughter of business tycoon James Goldsmith. The couple, who had two sons together, divorced in 2004. His second marriage to TV journalist Reham Nayyar Khan also ended in divorce.

His third marriage to Bushra Bibi, a spiritual leader whom Khan had come to know during a visit to a 13th-century shrine in Pakistan, reflected his deep interest in Sufism – a form of Islamic practice that focuses on spiritual union with God. Emphasizes closeness.

Once in power, Khan embarked on his plan to build a “welfare” state, which he said was an ideal system in the Islamic world some 14 centuries earlier.

But his anti-corruption campaign was heavily criticized as a tool to sideline political opponents – many of whom were jailed for corruption.

Pakistan’s generals also remained powerful and military officers, retired and serving, were placed in charge of more than a dozen civilian institutions.

Even after being injured in an attack on his convoy in November, the 70-year-old has shown no sign of slowing down as he led a protest march in Islamabad demanding general elections.

Khan had postponed for months to arrest He has several cases registered against him including charges of inciting mobs to violence. There were massive protests against previous attempts to arrest him.

Khan was ousted as prime minister in April last year amid public frustration over high inflation, a mounting deficit and endemic corruption, which he had promised to root out.

The Supreme Court overturned his decision to dissolve parliament, and his defection from the ruling coalition meant he lost the vote of no confidence that followed.

This put him on a long list of elected Pakistani prime ministers who have failed to see out their full terms – none since independence in 1947.

In 2018, the cricket legend, who led Pakistan to its only World Cup win in 1992, rallied the country overseas behind his vision of a corruption-free, prosperous nation. But the firebrand nationalist’s fame and charisma were not enough.

Criticized for being under the thumb of the once-powerful military establishment, Khan’s ouster came after deteriorating relations between him and the then army chief General Qamar Javed Bajwa.

The army, which has had a major role in ruling Pakistan for nearly half its history and gaining control of some of its biggest economic institutions, has said it is neutral towards politics.

sudden rise

But according to local polls, Khan is again among the most popular politicians in the country.

His rise to power in 2018 comes two decades after he first launched his political party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), or Pakistan Movement for Justice Party, in 1996.

Despite his fame and status as a hero in cricket-mad Pakistan, the PTI languished in Pakistan’s political jungle, winning no seats other than Khan’s for 17 years.

In 2011, Khan began attracting huge crowds of young Pakistanis disillusioned by local corruption, chronic power outages, and crises in education and unemployment.

He gained even more support in the following years, with educated Pakistani immigrants quitting their jobs to work for his party, and pop musicians and actors joining his campaign.

His goal, Khan told supporters in 2018, was to transform Pakistan from a country with “a small group of rich and a sea of poor” to “an example for a humanitarian system, a just system for the world, what is Islamic”. . welfare state”.

He was victorious that year, marking a rare ascent to the pinnacle of politics by a sporting hero. However, observers cautioned that his worst enemy was his own rhetoric, which sent supporters’ hopes sky high.

playboy to reformer

Born in 1952, the son of a civil engineer, Khan grew up with four sisters in an affluent urban Pashtun family in Lahore, Pakistan’s second largest city.

After a privileged education, he went to the University of Oxford where he graduated with a degree in Philosophy, Politics and Economics.

As his cricket career flourished, he developed a playboy reputation in late 1970s London.

In 1995, he married Jemima Goldsmith, daughter of business tycoon James Goldsmith. The couple, who had two sons together, divorced in 2004. His second marriage to TV journalist Reham Nayyar Khan also ended in divorce.

His third marriage to Bushra Bibi, a spiritual leader whom Khan had come to know during a visit to a 13th-century shrine in Pakistan, reflected his deep interest in Sufism – a form of Islamic practice that focuses on spiritual union with God. Emphasizes closeness.

Once in power, Khan embarked on his plan to build a “welfare” state, which he said was an ideal system in the Islamic world some 14 centuries earlier.

But his anti-corruption campaign was heavily criticized as a tool to sideline political opponents – many of whom were jailed for corruption.

Pakistan’s generals also remained powerful and military officers, retired and serving, were placed in charge of more than a dozen civilian institutions.