He had joined Morgan Stanley in the heady days of 2009, when the big banks were trying to bail out taxpayers and quell public anger. But four years later, the temper was waning and ambition was the order of the day.

“It really felt like, for the first time, jobs and careers weren’t defined in terms of the financial crisis,” Diop said. “We have gone beyond this now. And now it’s time for us to make new deals. In the years that followed, his rise as managing director found a new upswing. He helped broker a multibillion-dollar deal with SoftBank Group, whose risky investments defined an era, then closed a massive SPAC merger at the height of that rush.

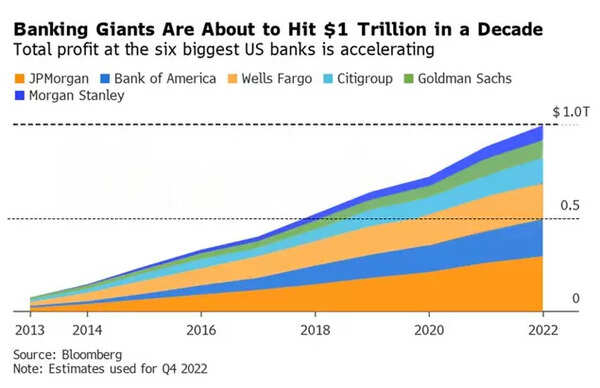

Diop didn’t know it, but he was playing a small role in something almost immeasurably lucrative: the first trillion-dollar decade for the six giants of American banking. It’s not $1 trillion of gross revenue, it’s net profit.

Such a stir seemed unlikely before the decade began, when Wall Street was the target of a global protest movement and politicians at both ends of the spectrum were boiling over bailouts or aiming to break up larger-than-failing lenders.

Instead they proceeded to outmaneuver corporate America so easily that JPMorgan Chase & Co., Bank of America The corp and even hobbled Wells Fargo & Co are on track to make more profit than all publicly traded US companies combined over those 10 years, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

citigroup, goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Morgan Stanley are not far behind. And together the six are set to make even more next year.

While much of the world’s attention was focused on the money amassed by Silicon Valley, banks were gaining momentum. There’s no way to explain how they pulled it off: Volatility juiced Wall Street’s business hulls, investment bankers like Diop rode a dealmaking boom, and Donald Trump boosted bottom lines by slashing taxes. Similarly, there is not a single reaction across the industry at milestones.

Betsy Duke, a former Federal Reserve governor who chairs Wells Fargo’s board until 2020, said, “Sometimes it makes sense that the fact that they made that much profit, and I don’t think that’s the case.” can be thrown at the financial system over the past 10 years. These banks have not only survived but have actually flourished.”

Through a decade of public anger at banks, tougher regulations, geopolitical havoc, the pandemic and some treacherous market swings, Duke said, the banks “were able to withstand them all, and not only withstand it but $ 1 trillion earned.”

Analyst projections show the six banks are fast approaching that milestone — $1 trillion over a 10-year period — and if they don’t reach the milestone later this month, they could in the first few weeks of 2023. Will reach sometime. However, it is not just the scale of profit that is so shocking, but the industry’s ability to move past scandals and flourish anew.

Ten years ago, JPMorgan, now the most profitable and valuable US bank by market capitalization, was in the doghouse after the London whale trading fiasco. Wells was the top of the Big Six, the most valuable and the only member of the group to pull in more than $20 billion. Although its earnings were later derailed by consumer abuse revelations, analysts expect it to be near that level again in 2023.

What hasn’t changed over the years is the broad outline of the business: banks sell stocks and bonds, trade financial instruments, advise on corporate acquisitions, manage funds, handle payments and lend. Back in 2013, some traders were already lamenting the casino-style risk-taking that 2010’s Dodd-Frank threatened, even though Washington was still figuring out the exact rules.

pay for scams

Banks had to pay to get out of the shadow of the global crisis. In 2014, Bank of America agreed to a record-breaking $16.7 billion settlement to end an investigation into shoddy mortgage practices, surpassing JPMorgan’s $13 billion. By then, some banks were mining new veins of profit that ran them into trouble.

Employees inside Wells Fargo, under pressure to meet sales targets, set up millions of accounts for customers who didn’t ask for them, the most famous of a series of scandals that eventually engulfed most of its businesses. And in Malaysia, Goldman Sachs raised billions of dollars in 2013 for a state-owned investment fund known as 1MDB, which was then stolen by a group including a former prime minister.

Former Goldman partner Robert Maas, a compliance executive, said, “My biggest regret over the last decade was not stopping the 1MDB transaction.” “Each issue was revisited several times in some cases, but the answers we finally got satisfy us.” Maas, who now teaches philosophy at New York’s Hunter College, said the firm was “misled by our own people, who were on bribes, in a way that we had no reason to suspect and we deny.” Couldn’t.” He wasn’t sure he learned any lessons, “besides trusting less.”

The magnitude of the gains make those mistakes look like hiccups. One man the industry can thank is Trump, taunted on the campaign trail before putting two Goldman alumni in charge of a tax overhaul that helped transform corporate profits. Banks that had gotten used to paying the government three in ten dollars paid themselves less than one in five for 2018. His tax bill went down from there.

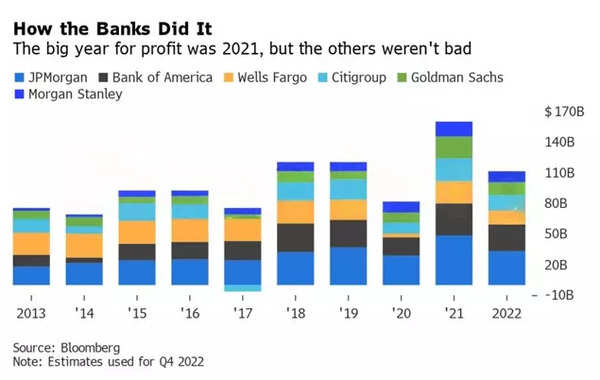

That year marked a new intensity for Wall Street developments. Banks that earned less than $70 billion in 2017 made $120 billion in 2018 thanks to tax cuts, rising interest rates and increased retail banking and dealmaking. Their combined wealth, which hovered around $10 trillion for years, began to grow rapidly.

The way top Wall Street lawyer H. Rodgin Cohen sees it, all of this shouldn’t be a surprise. “Banks can always be seen as winning with few exceptions because of the role they play in the economy,” said Cohen, now senior president at Sullivan & Cromwell LLP. “They are middlemen. They are borrowing and they are lending.

The decade was a difficult time to be a banker. Personnel spending for the six companies, which totaled about $148 billion at the start of the era before falling for a few years, rose to $154 billion in 2019, regardless of whether their total headcount actually fell. Went. JPMorgan boss Jamie Dimon, who had already become a billionaire, will eventually receive such a huge pay package that a proxy advisory firm asked shareholders to vote against it.

“One of the goals of a good society is that everyone, including those at the bottom, has enough to survive and thrive,” said Maas, a former Goldman fellow who now studies ethology. “I’m okay with people being paid well for producing products and services that increase the overall level of wealth in society, but only if we combine this with fair taxation and adequate social security to protect the bottom line.” May the people flourish.” He said he is not an expert enough to say whether the current tax and safety net is the right size.

Few things changed the Wall Street landscape in 2020 as profoundly as the advent of the pandemic. To stave off an economic catastrophe, the government launched relief programs for consumers and businesses, and the Fed bought trillions of dollars in assets. The market mayhem brought back the volatility that trading floors had been craving. Corporations are queuing up to borrow, raise capital or buy out weaker competitors.

Things were changing inside the banks too. When George Floyd was killed by police in May, Deep found himself inundated with messages from classmates and colleagues.

“It was from a real good place and well meaning, but at the same time you get 20 of those calls because you’re the only person that comes through,” he said. It was “tiring to be everybody’s Black friend at that point.”

That September, the news that Jane Fraser would become the first woman to run one of the big American banks caused cheers from her colleagues, but also disappointment at how long it took.

“I tried to change the industry from the inside out at the three biggest banks and I failed – there are shards of glass over my head,” said Anne Clark Wolff, a former executive at Citigroup, JPMorgan and Bank of America. Who founded Independence Point Advisors last year. “In 10 years at a large bank, the CEO never spent 10 minutes with me – and I was one of the most senior women.”

In early 2020, analysts were writing obituaries for Wall Street’s record profits. Instead, banks helped spark a boom of blank-check companies known as SPACs. Later, once the regulators stirred and prices fell, investors caught on.

Profits in 2021 were also helped by an accounting move: Banks felt good enough about the economy, thanks to government intervention, to release some of the reserves they had set aside in case of debt reduction. The Big Six made more profit in 2021 than in 2013 and 2014. Even when Russia invaded Ukraine this year, the chaos helped traders defy expectations of tough times.

Comparing the last 10 years’ profits eclipses those of the last decade, even if you take into account inflation and scale. bank merger during the financial crisis.

Yet other corporate titans, especially those in Silicon Valley, have done too well for Wall Street to claim a monopoly on success. Apple Inc. alone. earned over half a trillion dollars. Microsoft, Berkshire Hathaway and Alphabet topped JP Morgan, followed by Exxon Mobil, Bank of America and Wells Fargo.

Banks will attribute some of their gains to innovation, after investing in tech platforms and better offerings including credit card rewards. They have also helped companies tap capital markets to grow the economy. And they have maintained some gains to make a repeat of 2008 less likely, adding more than $200 billion to their capital buffers over the past decade.

Critics will argue that Banks did not do it alone. Many of them would not have survived in 2008 if it were not for taxpayer aid, and those buffers are a result of tighter capital rules, sometimes imposed over the vehement objections of bankers. Furthermore, it was another government intervention that propped up the economy during the pandemic, generating record profits. In other knocks: Some banks have focused on a smaller segment of customers, limiting opportunities for many communities, and have been slow to pass on rate hikes to savers, betting that customers will pass on to smaller rivals. Will not run away

Cohen said that ultimately the fate of banks depends on the health of their customers. His epic profits will plummet “if the economy hits a recession, a real recession,” he said.

Diop’s career shows potential pitfalls. Two major mortgage companies he helped bring to the public markets during the pandemic are down more than 50%, hit by high interest rates and economic worries.

Even when the market was buoyant, Diop worried about how things would look if the mood changed. “But you can’t be different for every deal,” he said. This year, he left Morgan Stanley to become an executive at Hooray, a media company run by actor and producer Issa Rae, his sister.

“I actually already miss it a little bit,” he said. “I miss finding out what’s next.”